Down To Earth speaks to prominent Punjabi poet about the Chenab as the inauguration date of the bridge over it nears

Prime Minister Narendra Modi will soon inaugurate an engineering marvel that India can be proud of: A steel and concrete arch bridge high over the mighty Chenab river in the Himalayas.

The bridge has been built at a height of 359 metres above the Chenab between Bakkal and Kauri. It is located in the Reasi district of the Jammu region, an area also known as the Chenab Valley.

It will be the highest railway bridge in the world. The bridge will mark the culmination of the national project to connect the Kashmir Valley to the rest of the country by rail. Trains will now be able to go right up to Baramulla, on the edge of the Kashmir Valley.

The project was a formidable one given the challenging terrain. But strategic value and engineering aside, the river the bridge fords is one of the most storied and legendary in India and South Asia. It especially has a prominent pride of place in the consciousness of the Punjabi people, among whom it has left an indelible imprint.

The Chenab is also one of the oldest rivers in South Asia. It is mentioned in the Rig Veda as Askini (‘dark coloured’). Formed by the confluence of the Chandra and Bhaga rivers in the Lahaul-Spiti district of Himachal Pradesh, it flows southwest into Pakistan, meeting first the Jhelum, then the Ravi and finally the Satluj. The united stream, the Panjnad (‘five rivers’) meets the Indus, which flows into Sindh and then the Arabian Sea near Karachi.

Despite being a fabled watercourse, the Chenab does not register as much on the national consciousness as say, the Ganga and Yamuna. Its waters (like those of the Jhelum, Ravi, Beas, Satluj and Indus) are also constantly feuded over by India and Pakistan, although the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty gives the right of using them to Pakistan.

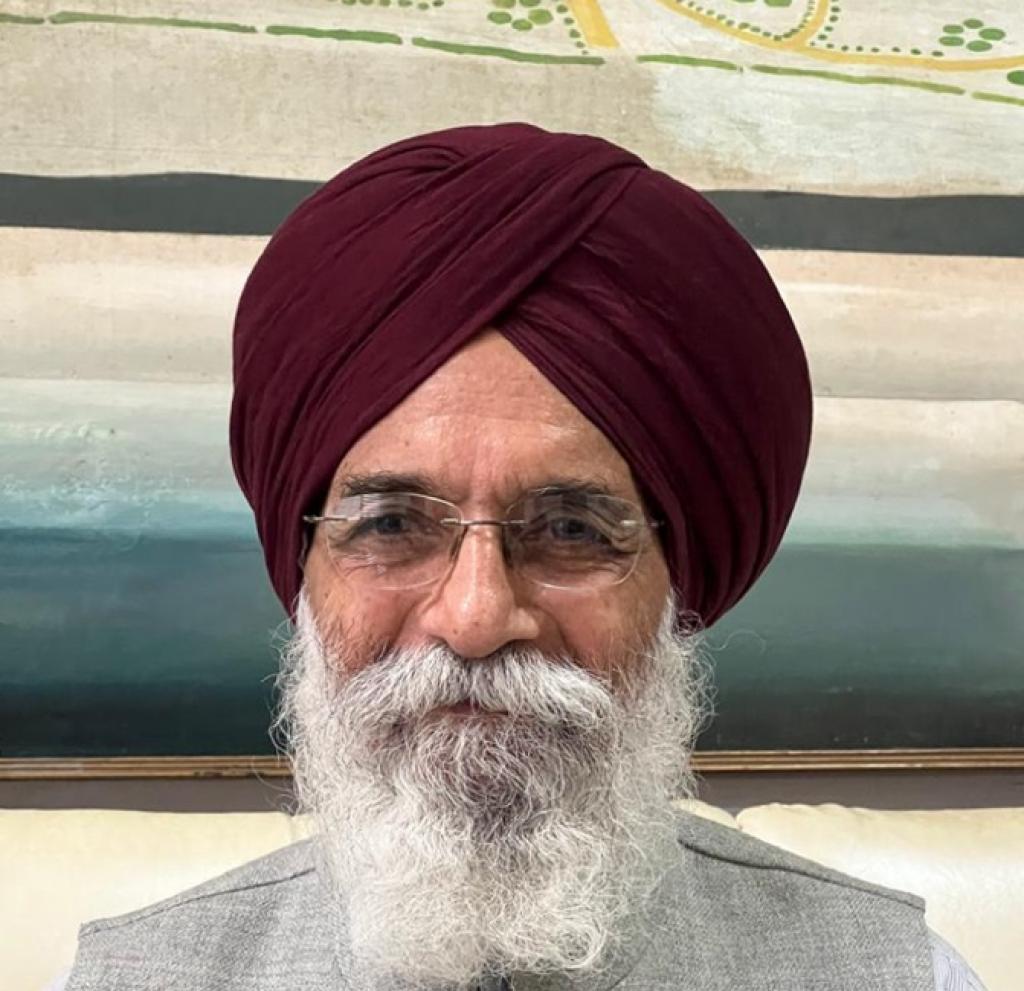

Down To Earth spoke to Surjit Patar, one of the foremost names in Punjabi literature, about the cultural impact of the Chenab on poetry and prose; its survival in these times of climate change and its place in today’s India, where most of it does not flow.

Patar was born in 1945 in Pattar Kallan, a village in Jalandhar district. He is a recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Award and the Padma Shri. Edited excerpts from the interview:

Rajat Ghai (RG): Why has the Chenab inspired the romance genre in Punjabi poetry and prose among all five rivers of the Punjab? Also, what has been its consequent impact on Punjabi consciousness?

Surjit Patar (SP): Indeed, the Chenab occupies the lion’s share of mentions in Punjab’s poetry and literature. In the tragic romance or Qissa of Heer-Ranjha, the eponymous hero Ranjha reaches the town of Jhang from his native village of Takht Hazara after fording the Chenab. It is on the banks of the river that he meets Heer for the first time. They meet in the woods on the riverbank.

In another popular Qissa, that of Sohni-Mahiwal, the heroine Sohni uses a clay pitcher to swim the waters of the Chenab in order to meet Mahiwal. In the end, a jealous relative replaces her pot with a freshly-made one, which breaks down, leading her to drown. Mahiwal swims to save her. But he too drowns in the raging waters.

Surjit Patar. Photo: Diwan Manna

The inspiration provided to Punjabi songs by the Chenab is unmatched by any of its counterparts. I remember Aakashwani producing a programme for listeners from Lehnda Punjab (Pakistani Punjab) with the tagline Lang Aaja Patan Chana Da Yaar (Come across over to the banks of the Chenab, O beloved), based on the lines of a popular folk song. This line was also the signature tune for the Indo-Pak Games.

Amrita Pritam wrote beautifully about the river at the time of the Partition. She wrote: Ajj Bele Lashaan Te Lahoo Di Bhari Chenab (The river of lovers is filled with corpses and blood today).

Prominent Punjabi poet Professor Mohan Singh, in a poem almost written as a last will and testament, asked his ashes to be scattered in the Chenab instead of the Ganga, since it is the ‘river of love’.

Post-Partition, Singh wrote in a poem: Ganga Banawe Devte Te Jamuna Deviyan, Ashiq Magar Bana Sake Paani Chenab Da (The Ganga creates gods, the Yamuna goddesses. It is the Chenab’s water though that makes lovers).

RG: Today, it is a transboundary river, bitterly feuded over by 2 countries. Has this affected its place in Punjabi literature post-1947 in any way?

SP: The Chenab’s place in medieval Punjabi literature is uncontested. I have mentioned how Amrita Pritam and Mohan Singh used the river as a metaphor in their works during and post-Partition.

Another poet, Devendra Satyarthi, writes: Nahi Reesan Chenab Diyan, Bhawein Sukki Vaghe (The Chenab is peerless, even if it flows dry). Pash (Avtar Singh Sandhu), a famous Communist poet of Punjab, wrote: Chenab Da Ashiq Neer Ki Jaane, Mere Phull Satluj Wich Bahane. Being influenced by radical far-left ideas such as social revolution, Pash said his ashes were to be immersed in the Satluj, rather than the Chenab.

Harinder Mehboob, born in an area of Pakistan along the Chenab, who migrated during 1947, wrote a compendium of seven poetry books which he titled Chenab Di Raat (Night of the Chenab). It won the Sahitya Akademi Award.

I was 2 when the Partition happened. I have also mentioned the Chenab in my works, though in a different vein.

In one of my compositions, I write: Har Ik Kol Si Apna Alag Alag Paani, Chenab De Kande Lahore De Shauqueen Mile. It is a satire on the state of the province’s rivers that were loved by all Punjabis — Muslim, Sikh and Hindu. But now they are horribly polluted.

After reading a book some years ago about the horrors faced by Punjabi refugees fleeing the Partition, I wrote a composition where I again used the five rivers as metaphors. About the Chenab, I wrote: Naal Namoshi, Paani Paani Hoye Chenab De Paani, Nafrat De Wich Dubb Ke Mar Gayi Har Ik Preet Kahaani (The waters of the Chenab flow ashamed; every love story has drowned in hate).

The river still has importance in Punjabi poetry and consciousness. But today, besides reminding us about the classic romances, it also reminds about sadness and the deep pain of separation.

I wrote once: Kahe Satluj Da Paani, Aakhe Beas Di Rawani, Saadda Jhelum Chenab Nu Salaam Aakhna (The Satluj and Beas send their Salaams to the Jhelum and Chenab).

RG: Today, the Himalayas, where the Chenab and several other rivers (Ganga, Indus, Brahmaputra) originate, are losing their snow and ice due to global warming. The rivers of Punjab are already in a sorry state due to damming. What impact, in your view, will a dying Chenab have on romance in Punjabi literature for coming generations?

SP: The rivers of Punjab, or for that matter, all rivers in India or even abroad, today remind us of the rapacious greed and selfishness of Man. Indeed, the new literature emerging in Punjab does make mention of all this: Our consumerist lifestyles, the short-sightedness of those who lead us. The rivers that once reminded us of love, today remind us of the worst in ourselves.

I once wrote on this issue:

Maatam, Hinsa, Khauff, Bebasi Te Anyaa

Aey Ney Ajj Kal Mere Panjaan Daryawaan De Naa

Jo Hunde San Jhelum, Satluj, Ravi, Beas Te Chana

Lament, Violence, Terror, Helplessness and Injustice

These are the names of my five rivers today

Which were Jhelum, Satluj, Ravi, Beas and Chenab once.

But I also expressed a note of hope in the last line:

Par Jede Ik Din Howange Raag, Shayari, Husan, Mohabbat Ate Nya

But which will one day be Music, Poetry, Beauty, Love and Justice

RG: Why has the Chenab (or indeed any of the Punjab rivers) not had an impact on public consciousness outside Punjab? Is it because it is a river that flows in a ‘peripheral’ part of the country, away from the ‘mainstream’?

SP: One should remember that mentions of the Ganga in comparison to the Punjab rivers in the Rig Veda are very less. The rivers mentioned most in one of the oldest works of poetry in the world not being given as much importance as is their due is telling. By doing this, we are leaving out on a very important part of our own history. This is seen in our popular culture where we know the names of Heer-Ranjha and Sohni-Mahiwal but do not know the name of the river where these stories are set.

The Partition is also a very big factor in this. Pre-Partition Lahore was a big centre for arts and culture. You had Krishan Chander, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Amrita Pritam and Saadat Hasan Manto, all in that city. Bombay was not what it is today. Lahore was the hub of filmmaking. But Partition put an end to all that. The majority of Punjabis (Muslims), along with rivers like the Chenab, are today part of Pakistan. Hence, the cultural impact is bound to be less outside Punjab.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.