Since 2018, Maharashtra is running a first-of-its-kind project to help farmers switch to climate change-resilient structures and practices. Implemented in 16 of the state’s 36 districts, this Project on Climate Resilient Agriculture (pocra), also named Nanaji Deshmukh Krushi Sanjivani Prakalp, is labelled the country’s biggest such initiative. However, data shows that a vast majority of funds have gone to just a few districts and types of interventions.

“pocra started with a budget of Rs 4,000 crore. No other state has such a climate-resilient agriculture project,” Vijay Kolekar, agronomist and soil science specialist, department of agriculture, Maharashtra, tells Down To Earth (DTE). Of this amount, 70 per cent is a World Bank loan, while 30 per cent is the state government’s share.

The project is based on direct benefit transfer. Farmers, communities, farmer producer organisations/companies (FPOS/FPCS) and self-help groups (SHG) can register on the official website — dbt.ma- hapocra.gov.in — and file an application to receive funds for 25 types of interventions (see ‘Interventions allowed’ on p38 and ‘Target districts’ on p39). These include drip irrigation, warehouse construction, seed production and agricultural mechanisation.

“We have adopted a farmer-centric approach, where the farmer tells us what he/she wants instead of the state telling them what to do,” says Umesh Jadhav, project specialist, Nanaji Deshmukh Krushi Sanjeevani Prakalp, Buldhana — one of the 16 districts where pocra is implemented.

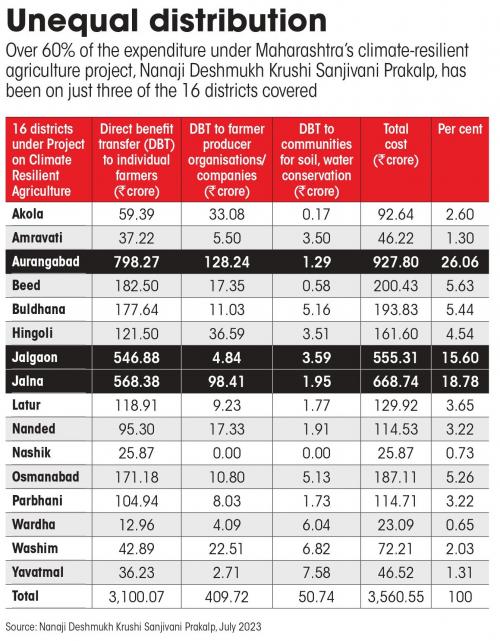

The scheme has resulted in a few districts garnering a large chunk of the funds (see ‘Unequal distribution’). Maharashtra agriculture department data accessed by Delhi-based think tank Centre for Science and Environment showed that more than 60 per cent of the funds (Rs 2,151.85 crore of Rs 3,560.55 crore) have gone to just three of the 16 districts: Aurangabad (26.1 per cent), Jalna (18.8 per cent) and Jalgaon (15.6 per cent).

“This means only a limited number of farmers in a select few districts are benefitting, while the agrarian crisis is across Maharashtra,” says Wardha-based Vijay Jawandhia, founding member of a Shetkari Sanghatan, a farmer organisation. Maharashtra has 15.29 million operational farm landholdings, as per Agriculture Census 2015-16. But less than 1.22 million farmers have registered on the pocra website. The number of farmers in the 16 districts under pocra is about 5.8 million, as per the project documents.

Apart from a majority of the funds being spent on a couple of districts, the omission of some districts is also difficult to explain. In 2017-18, the government submitted the project proposal to the World Bank. The document listed 15 climate-vulnerable districts to implement the project. But it did not give details of the criteria for the selection. The government added another district, Nashik, later.

If one goes by district-level assessment of agriculture’s vulnerability to climate change, published by Indian Council of Agricultural Research-Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture in 2013 and 2019, Ahmednagar and Nandurbar figure in top 10 vulnerable districts. But these two districts have not been included under Pocra.

Even if one goes by just the 2013 assessment, which was the latest district-level government survey available when the scheme was being planned, then five of the top 10 vulnerable districts — Solapur, Ahmednagar, Nandurbar, Sangli and Dhule — are not included under Pocra. “The project is for rain-fed, drought-prone, salinity-affected districts. Of the selected districts, 14 were also suicide-prone,” says Kolekar.

“The selection of districts is a political decision,” says Raju Shetti, leader of Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghatana, a farmer organisation based in Maharashtra.

Data also shows that 77 per cent of DBT to individual farmers (Rs 2,404.9 crore of R 3,105.8 crore) has been spent on just three of the 25 interventions — drip irrigation (52 per cent), shade net house (14 per cent) and sprinkler irrigation (11 per cent). “What happens is that farmers prefer interventions that are easy to install and produce quick results. They are also influenced by what their neighbours and the village in general is using. Therefore, the funds have gone to just a few interventions,” explains a Pocra official, on condition of anonymity.

This is not to deny that the farmers who have received the as- sistance have actually benefitted. Down To Earth travelled to three pocra districts — Buldhana, Jalgaon and Jalna — in August 2023 and found many farmers who were appreciative of the project.

Take the case of Usha Bhoite, a farmer owning about 5 hectares (ha) in Betawad Bk village of Jalgaon. Bhoite says she got drip irrigation installed on 2 ha, with 75 per cent funding under the Nanaji Deshmukh Krushi Sanjivani Prakalp project in 2021. “This year, the rain was delayed. The cotton sown in 2 ha that had drip irrigation survived, while seeds in the other 3 ha did not germinate, resulting in a loss of Rs 60,000. The project helped me get a good crop on at least a part of my land,” she says.

“I have set up a shade-net house with the help of money I received under pocra. This has helped me increase my profits from Rs 25,000 per acre (1 acre equals 0.4 ha) to Rs 4-5 lakh per acre,” says Yogesh Vithobakhrat, a 33-year-old farmer from Waghreul Jahangir village of Jalna.

Shade-net allows desired level of temperature, sunlight and moisture to reach crops, creating an ideal microclimate for optimum output. “It cost Rs 21 lakh per acre to install shade-net. I got a subsidy of 75 per cent. I could not have done this on my own,” says Vithobakhrat, who grows capsicum, chillies, tomatoes and cucumber. “The net also prevents pest and attacks by nilgai,” he adds.

“I got a pond constructed with a subsidy of Rs 3.2 lakh under the project. The pond has helped me farm even during the six months of the year when the borewell runs dry. This has increased my profits from Rs 40,000 to Rs 1 lakh last year,” says Pandurang Tambekar of Shivanitaka village, Buldhana.

While practices like drip irrigation and farm ponds are good, the crop production practices promoted under pocra are based on the same old chemical- and input-intensive agriculture model (for instance, high on capital and machinery), which has proven unsustainable. Moreover, there are huge concerns of scalability and sustainability.

For instance, shade-net is costly to install and lasts only around five years. Agriculture officials also say that shade-nets reduce soil productivity over time, since soil becomes hard and high in salt content, with reduced water-absorption capacity. Under pocra, officials have also been undertaking training and pro- motional activities that focus on techniques like zero tillage (no ploughing of field), broad-bed fur- row (to protect crop from waterlogging), and inter-cropping (growing two or more crops in proximity).

While the latter two are ecologically fine, zero-tillage requires use of weedicide at least three times in a season. Apart from ecological damage, it also increases severity or reemergence of crop diseases, which make it unsustainable.

As the first phase of the scheme draws to a close, the next phase of pocra is likely to start. “The government has given in-principle approval to start the next phase from June 2024, with a budget of Rs 6,000 crore, covering additional five districts: Nagpur, Bhandara, Gondia, Chandrapur and Gadchiroli,” says Kolekar.

“We wish all farmers could get support under pocra. We are receiving lots of requests from public representatives to implement it in their area. However, applications are being rejected now, as the first phase of pocra will end in 2024,” says P S Sawale, agriculture assistant, pocra, Jalna.

This was first published in Down To Earth’s print edition (dated October 16-30, 2023)

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.