Policies and urban planning frequently disregard the needs of the urban poor, resulting in an unequal distribution of resources between residents of formal and informal cities

This article is the first in a three-part series on unplanned settlements, urban planning, and the challenges related to water, sanitation, and stormwater management that are acutely felt in large, dense, unplanned settlements in cities of the global south, with research centred on Delhi.

Urbanisation is one of the four ‘demographic mega-trends’ identified by the United Nations, along with population growth, ageing, and international migration.

According to a 2019 report by Asian Development Bank (2019), the global urban population has risen dramatically, from 751 million people in 1950 (30 per cent of the world’s population) to 4.2 billion in 2018 (55 per cent of the world’s population).

This figure is projected to increase to 5.2 billion in 2030 (60 per cent of the world’s population), and 6.7 billion in 2050 (68 per cent of the total global population). The report also notes that increased urbanisation could lead to growing income disparities, with a widening gap in job prospects between those in formal and informal urban sectors.

Read more: How Delhi Master Plan 2041 misses the bus in every aspect

The 2021 report on urban competitiveness on a global scale highlighted that many urban regions struggle to access clean water, adequate sanitation, healthcare facilities, and educational opportunities.

The Indian scenario

According to the 2011 Census, India’s urban population increased from 27.7 per cent in 2001 to 31.1 per cent (377.1 million) in 2011, at a rate of 2.76 per cent per year. However, since the 1990s, the urbanisation trend has shifted from large Tier 1 cities to medium-sized towns.

Migration contributes to urbanisation, and the reasons for this have been investigated, including marriage, employment, education, security, lack of security, and push and pull factors. Migrating populations will occupy available land, resulting in informal settlements and unplanned colonies built by individuals or small groups of builders.

In urban areas, the slum population represents the lowest-income strata, and in large metros — such as Mumbai, Delhi or Bengaluru — where buying land from small builders is not possible, slums are more endemic. According to a 2022 article by newspaper The Times of India, there are 2,400 and 675 slums in Maharashtra and Delhi, respectively.

Informal and unplanned settlements

Urban settlements in India are broadly classified into planned and unplanned settlements. Planned settlements are those that have been constructed and developed by government agencies or housing societies in accordance with approved plans. Physical, social, and economic factors, among others, are considered when developing such colonies.

On the other hand, unplanned settlements are those that have come up illegally, either on government land or private land, in a haphazard manner. They have both permanent or semi-permanent and temporary structures edging the city drains, railway tracks, low-lying flood-prone areas, occupying agriculture land and green belts in and around the city.

A significant number of the residents of unplanned settlements work in informal sector, which would not be paying them adequately, thus, out of compulsion, they tend to settle in areas where basic amenities are either lacking or completely unavailable, with the hope of reducing their living costs, including rent, in areas like slums, jhuggi jhopri (JJ) clusters, unauthorised colonies, etc.

Once established, unplanned settlements continue to expand without any supervision from the government, posing further spatial problems.

Informal and unplanned settlements are considered illegal and denied formal services of water supply and sanitation. An outbreak of cholera and gastroenteritis as late as 1988 reportedly claimed more than 150 lives in east Delhi slums, leading to improved municipal supply of water and eventually to sewerage.

The extent of the large scale of urban informal settlements and informal work force was evident during the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020, when a large-scale return of migrants from Mumbai, Delhi and other cities was visible.

Delhi scenario

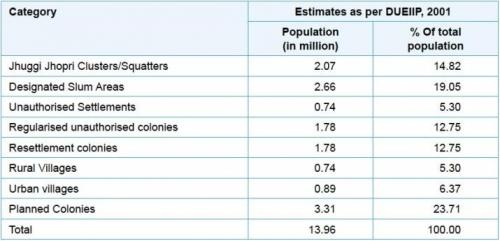

As per the Economic Survey of Delhi (2002), human settlements have been classified into eight different types. The categories are as follows:

Read more: Global South water-sensitive cities: Framing the discourse

Informal settlements in Delhi (2001)

Data: Delhi Urban Environment and Infrastructure Improvement Project, 2001

Planned colonies constituted less than 24 per cent of the total population of Delhi in 2002. Since the last two decades, the percentage of population residing in planned colonies has been even smaller.

According to the 2011 Census of India, Delhi’s urban population was 16.3 million, with a decadal growth rate of 21.2 per cent from 2001 to 2011. Out of 16.3 million urban population, 7.22 million were migrants. With the continuation of the present population trend, the total population of national capital territory of Delhi by 2021 would be 22.5 million.

In 2014, Delhi government carried out a survey of slums and JJ colonies, estimating that 0.33 million households (approximately 1.7 million people) lived there, which is around 10 per cent of Delhi’s total population. Out of this 0.33 million, about 0.30 million are migrants.

According to 2017 research, the majority of people who migrate from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, Rajasthan, Punjab, and other states to Delhi do so in search of higher-paying jobs, a process known as inter-state migration. In contrast, some people, particularly farmers, migrate to Delhi during the off seasons in search of work—a phenomenon known as seasonal migration. According to the 2011 Census of India, 2.03 million people moved to Delhi as part of the seasonal migration process.

The large number of unplanned settlements in Delhi is caused by a significant supply and demand imbalance for land, housing, and related infrastructure. Policies and urban planning frequently disregard the needs of the urban poor, resulting in an unequal distribution of resources between residents of formal and informal cities.

As per the 2021 Master Plan of Delhi (MPD), the goal of providing housing for everyone by 2022 required construction of or improvement of 4.8 million houses. The proportion of these houses designated for economically weaker sections (EWS) would be 54 per cent of the overall total.

Delhi required 2.4 million fresh housing units by 2021, as per the MPD, with adequate infrastructural facilities like water and sanitation.

|

Type of unplanned settlement

|

Total number

|

Land area

|

|

Unauthorised colonies

|

Colonies: 1,797; Population: 4 million

|

Illegal colonies in violation of Master Plans, no clear land title

|

|

JJ settlements

|

JJ Basti 755 (dwelling units required: about 0.3 million); Population: 1.7 million

|

Encroached on public land: state government: 30 per cent; central government: 70 per cent

|

|

Resettlement colonies

|

Colonies: 82 (45 + 37); Plots: 267,859; Population not specified

|

Incorporated within the expanded city with good shelter consolidation but without adequate services

|

What is clear is that unplanned urbanisation has become a norm for most Indian cities and most Global South countries. It has taken the form of ultra-rich gated communities on one hand and large, dense, unplanned informal settlements and slums on the other.

Provision of water, sanitation and stormwater management are challenges everywhere now. It impacts the economically poor residents of dense, unplanned settlements more than others.

The second article in this series will delve on urban planning and why it has failed to prevent the emergence of dense unplanned settlements in urban India.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.