Latest sex ratio numbers, accessed by DTE through the Right to Information Act suggested the situation has again started to worsen in the state

Nidhi became anxious earlier this year when she realised that she was pregnant for the second time. Already a mother of a girl child, she knew her family expected a son this time around. So her husband, who works at a private hospital in Haryana’s Faridabad district, decided to illegally determine the gender of the unborn child. The couple visited a clinic in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, which discloses the gender for money. They were relieved once the clinic confirmed

that the unborn child was a boy.

Maan Singh, the government official responsible for clamping down on pre-birth gender determination in Faridabad, said his team has already carried out 13 raids this year. The last raid was conducted at a private clinic in Chhanyasa village in Uttar Pradesh after his team got a tip-off that a woman from Faridabad had travelled there to get her girl child aborted.

“The woman fled the clinic, so we traced her on the basis of her records at the clinic. By the time we reached her house, she had already gotten the abortion done at another clinic,” said Singh. He is now trying to convince the woman and her family to share the formation of the illegal clinics they visited for gender determination.

Haryana has historically had one of the lowest sex ratios in the country, but this story changed — only briefly — for the better in 2015 after the launch of the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao scheme that has a mandate of improving the sex ratio at birth by two points each year. The latest numbers, accessed by Down To Earth (DTE) through the Right to Information Act, suggested that the situation has again started to worsen in the state.

In 1901, the state had 867 females per 1,000 males in its total population, as per the Statistical Handbook of Haryana 2020-21. Over 100 years later, as per Census 2011, the state’s sex ratio remained equally worrying at 879 females per 1,000 males. Haryana’s sex ratio at birth, which reflects pre-birth discrimination, jumped from 876 in 2015 to 900 in 2016.

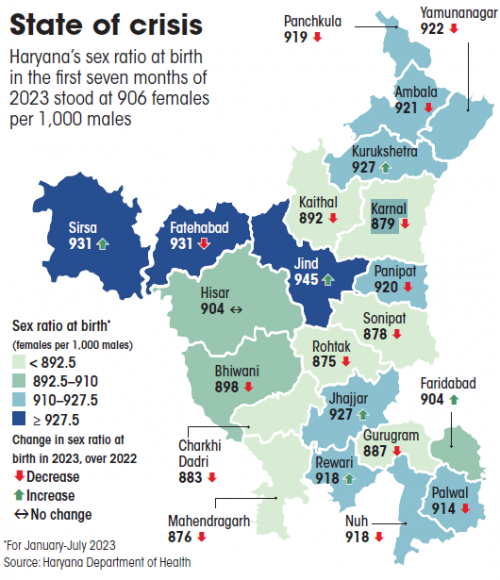

The upward trend continued until 2019, when the state’s sex ratio at birth peaked at 923. Ever since, the ratio has started to drop again. It reached 917 in 2022. In the first seven months of 2023, Haryana’s sex ratio at birth dipped to 906 female births per 1,000 male births. The sex ratio has dipped in 16 of the 22 districts in the state. Six districts reported more than a 20-point drop between 2022 and 2023.

“Such a huge decline only means that sex determination tests and girl child abortion has once again increased in the state,” said Singh.

Anisha Sharma, who teaches economics at the Ashoka University in Panipat, Haryana, and has authored several research papers on girl children in the country, said though the 2015 scheme temporarily arrested the decrease sex ratio, the situation for girls has never really improved. “The education levels among girls remained low and their mortality went up,” she said.

Missed opportunity

India banned prenatal sex determination in 1994 by enacting the Pre- Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, or pndt. Violations under the Act are cognisable (arrests can be made without a warrant) and non-bailable.

The number of raids and convictions under it increased after 2015 due to improved sensitisation and government focus. But over the years, the success of the Act and the scheme seems to have tapered.

Singh said that Haryana has “negligible” gender testing cases now. The problem lies in neigh- bouring states like Uttar Pradesh and Delhi that have not implemented the ban and the scheme properly.

“Many clinics are thriving in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Delhi,” said Singh.

His counterpart in Gurugram dis- trict of Haryana, Pradeep Kumar, said that these clinics operate in a complex fashion with several layers of intermediaries to avoid detec- tion. “They charge anything from Rs 25,000 to Rs 75,000,” said Kumar.

Harjinder Singh, senior medical officer at the Community Health Center of Khedi Kala village, Faridabad, said that the desire for a male child was traditionally more pronounced in the families belonging to the upper caste and wealthy. But now even people from other castes are indulging in this malpractice.

“On one hand sensitisation has helped, but on the other, people’s access to gender determination and abortion has increased manifold,” said R S Dahiya, retired professor from the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Research in Rohtak.

For instance, earlier, gender determination and abortions happened only in hospitals. Now they happen in vans with portable ultrasound machines. There are medicines and vaccines today that can cause miscarriage, he added.

A senior officer with Haryana’s health department said that the country’s recent revision of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, has increased female foeticide. Under the Act, abortions were earlier allowed within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. In 2021, this was revised to 24 weeks.

“Most abortions are done citing contraceptive failure. The real reason is that the couple do not want a girl child,” he said. He believes that the country must allow gender determination and make the process of abortions extremely difficult in the case of a girl child. “If the ban is lifted, people will go to registered clinics and hospitals,” he said.

This was first published in Down To Earth’s print edition (dated October 16-30, 2023)

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.