G7 failed to set concrete, reliable commitments in line with GST’s historic call on countries to transition away from fossil fuels

Ahead of the G7 Ministerial on Climate, Energy and Environment, host Italy, which holds the Presidency of the group this year, made it clear that a timeline to phaseout coal was high on the agenda. Although an agreement was seemingly reached, a deeper look into the final outcome exposed gaps that water down any strict targets.

The ministerial culminated in Torino, Italy on April 30, 2024 and a final communique was made public with details of agreements reached by the countries on key matters related to energy transition, climate finance and enhanced climate ambition.

Comprising the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Japan and Canada with the European Union as an unofficial member, the G7 group represents some of the wealthiest nations. The outcomes of its annual summit, therefore, are generally thought to trickle down and influence other country summits such as the G20 and the annual Conference of Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

COP28 in Dubai last year culminated in the outcome of the first ever Global Stocktake (GST) which served as a blueprint for the outcomes. The communique reaffirmed the members’ commitment to submit nationally determined contributions (NCD) aligned with GST, triple global renewable energy capacity and double energy efficiency.

Yet, G7 has failed to provide concrete, reliable commitments in line with GST’s historic call on countries to transition away from fossil fuels.

Unclear timelines, clear caveats

Italy’s reported push for an agreement among the countries seems to have resulted in a commitment to “phase out existing unabated coal power generation in our energy systems during the first half of 2030s or in a timeline consistent with keeping a limit of 1.5°C temperature rise within reach”. The lack of a specific target year, however, stood out. The latter half of the statement essentially allows the countries to extend the phaseout timeline past the 2030s as well.

This, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recommends that global coal use “has to fall by 67-82 per cent by 2030 for a 50 per cent chance of meeting the 1.5°C target”. Global climate politics dictates that from the lens of equity and fair shares, developed countries must lead this phaseout.

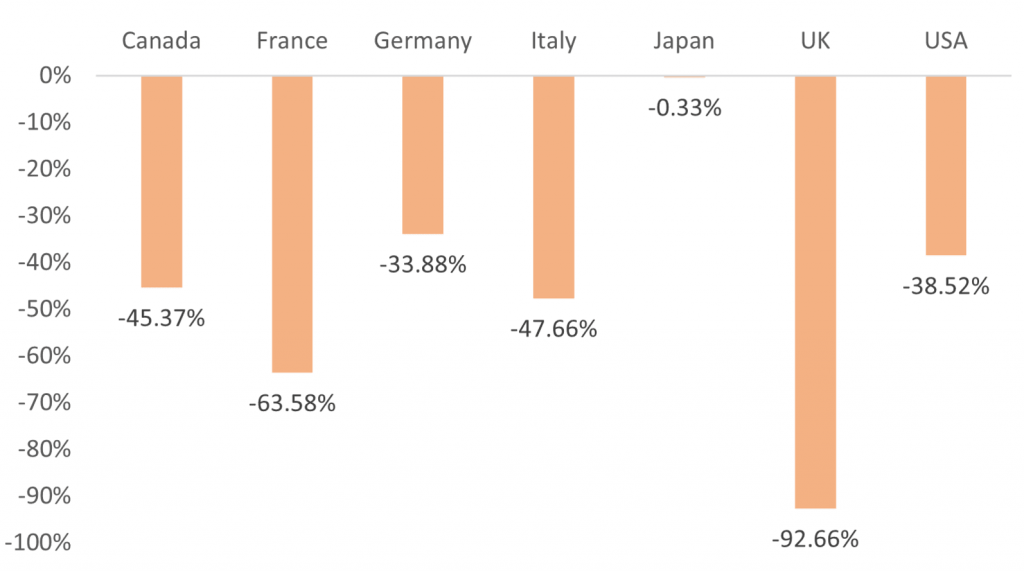

However, an analysis by Delhi-based think tank Centre for Science and Environment of reduction in coal usage in the G7 countries since the Paris Agreement in 2015 until 2022 showed that the UK is the only country to achieve this range at 93 per cent. France is the only other country at a reduction of more than 50 per cent. Japan has reduced 0.33 per cent. Their failure to arrive at a commitment to rapidly phaseout the fuel, is telling of the lack of urgency and leadership shown by the most advanced economies in achieving emissions reduction.

Reduction in coal for electricity generation (2015-2022)

Source: Ember, CSE Analysis

Of the seven member countries only the UK, France, Italy and Canada have had clear timelines for a coal phaseout. The US joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA) just last year, with a 2035 deadline. Germany has a timeline of 2038, with an option to bring this forward to 2030 “if conditions allow”. Japan has set no target and is the only country that is not a signatory to PPCA.

Past attempts to arrive at a coal phaseout year for the G7 have been unfruitful. In 2023, the G7 summit saw the UK and Canada wanting to set a date of 2030 for coal phaseout. The proposition was accepted by France but opposed by then host Japan, the US and the EU.

Internal politics set back action

The EU has to agree on such targets internally before accepting them at an international level. Its member state Poland depends on coal for 70 per cent of its power generation today and has a timeline of 2049 to phaseout the fuel. The 2030 deadline was, therefore, dubbed “not mature enough” by the EU.

Reports stated that domestic politics has been the biggest barrier to the US committing to a coal phaseout timeline. However, no new coal power plants have been built in the country since 2013.

Japan, by far the most coal-reliant of the group with a third of its electricity still generated from the polluting fuel, has been the biggest blocker to a concrete phaseout timeline. It can be surmised that the flexible language in the communique is meant to benefit Japan’s prolonged use of coal.

In 2023, the country pledged to stop the construction of new unabated coal power plants. This offers little reassurance. While carbon capture and storage in general is a highly contentious emission reduction solution, for Japan ‘abatement’ can mean many other forms. For example, the country has long advocated for the use of ammonia-coal co firing and is set to begin its first test of the technology in 2024. The technique involves burning coal with a mix of ammonia in an effort to reduce carbon emissions. In reality, however, the method is unproven, has high costs and comes with the risk of increasing life cycle GHG and CO2 emissions. Unsurprisingly, recent analysis has projected Japan to be reliant on coal for 29 per cent of its electricity even in 2033.

Lack of equity & fair shares

According to the International Energy Agency, staying on a 1.5°C aligned pathway requires advanced economies to phase out unabated coal by 2030. Looking past the absence of a specific timeline, the arbitrary “first half of 2030s” itself raises questions about whether the G7 countries are shouldering their fair share of the burden of being historical polluters.

At multilateral fora, developed nations have pushed for specific language on coal phaseout, citing it to be the most polluting fossil fuel. In 2021, G7 even committed to end financing of coal projects worldwide. Despite this, if the wealthiest nations are unable to agree on an end-date for coal, it is unfair to expect such a commitment from emerging and developing economies in the Global South, where most of the coal use today is concentrated.

Avantika Goswami, programme manager, climate change, the Centre for Science and Environment, said:

The G7 countries alone are responsible for close to half (42 per cent) of carbon dioxide emitted since 1900 and 39 per cent of fossil fuel consumption since 1965. As historical polluters, it is unacceptable that they are dragging their heels on phasing out the use of coal with a clear and urgent timeline.

“These countries also continue to heavily depend on oil and natural gas, despite possessing the resources to rapidly decarbonise their energy systems,” she noted. “This eats into the carbon space that developing countries ought to have access to as they improve prosperity and meet their developmental goals, and puts us on a path of planetary devastation.”

Moreover, the focus on ‘unabated’ coal power dilutes the G7’s commitment further since it creates a loophole for unreliable technologies like carbon capture and storage that have so far proved unsuccessful at capturing emissions at scale, Goswami added.

Commitments on other themes

The group has committed to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, with specific targets such as a 75 per cent reduction in global methane emissions from fossil fuels. On the other hand, in the context of energy security and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, they “stress the important role that increased deliveries of LNG can play and acknowledge that investment in the sector can be appropriate in response to the current crisis and to address potential gas market shortfalls provoked by the crisis”.

It is pertinent to note here that the GST outcome had specifically recognised the role of ‘transitional fuels’ in the fossil fuel phaseout. Multiple groups had raised concerns that this would enable countries to increase their use of natural gas.

On finance, the emphasis by G7 on mobilising public funds, grants and concessional finance is a welcome mention. However, the debt crisis of the developing world is under-acknowledged and there is no substantive commitment addressing this issue except a call for multilateral development banks to deploy non-debt creating instruments.

Drawing from the GST process, the communique mentioned supporting policies that help align financial flows with the goals of the Paris Agreement – an emerging point of contention between developed and developing countries on climate finance. The group’s priorities regarding the New Collective Quantified Goal, or post-2025 climate finance goal under negotiation within UNFCCC, were also expressed in the communique.

On high-integrity carbon markets, the group listed multiple priorities. These include following the development of Article 6 framework within the COP process, capacity building for nations developing carbon markets as well as seeking innovative approaches in carbon markets and carbon pricing to secure climate finance from public and private sectors. Specifically on carbon removal, the group committed to increase demand and develop certification standards.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.