On Babasaheb’s birth anniversary, DTE speaks to the head, department of history, at Ambedkar University, Lucknow on Ambedkarite environmentalism

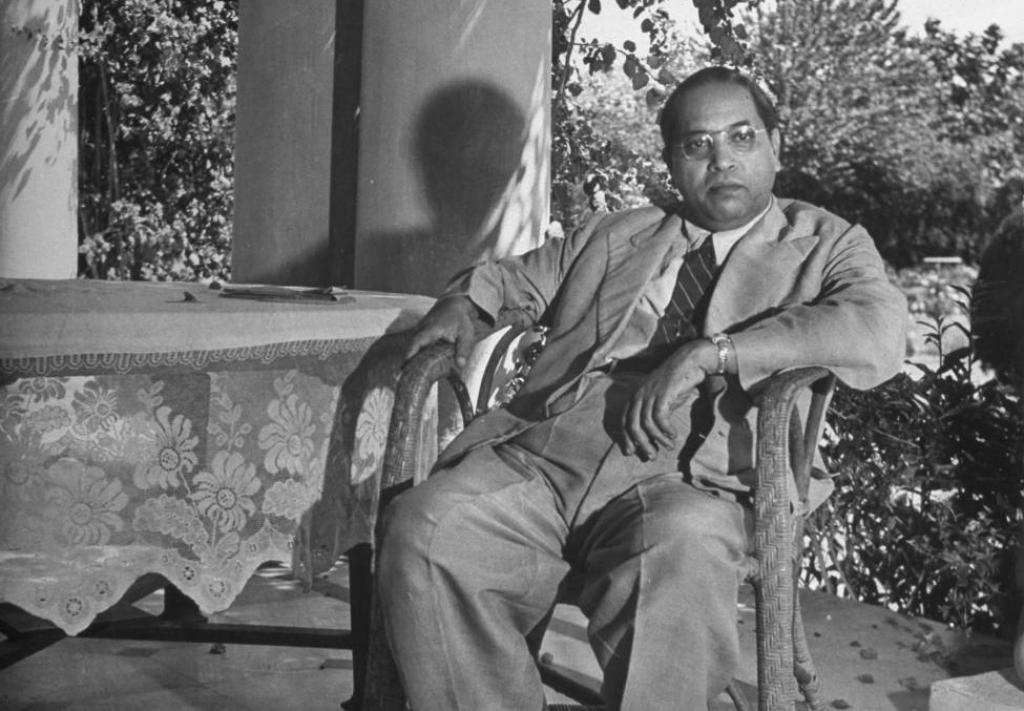

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar at his home, Rajgriha, in Dadar, Bombay circa 1946. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. CC 1.0

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar at his home, Rajgriha, in Dadar, Bombay circa 1946. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. CC 1.0

As India once again pays homage to Babasaheb Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar on his birth anniversary, Down To Earth (DTE) decided to explore the ecological dimensions of Ambedkarite philosophy.

Babasaheb’s views on socio-economic, political, constitutional and administrative issues are enshrined in the Indian Constitution, which he helped steer and frame.

But linked to that was the persona that most Indians do not know about: that of Ambedkar the environmentalist.

It may appear surprising to many but B R Ambedkar held strong views on the relationship between humans and Nature and the allocation of natural and ecological resources.

To learn more, DTE spoke to V. M. Ravi Kumar, head, Department of History at Ambedkar University, Lucknow. An expert in this field, Kumar talked about what makes Ambedkarite environmentalism unique and how it can help the world tackle the ongoing climate emergency. Edited excerpts:

Rajat Ghai (RG): How is Dr B R Ambedkar connected to environmentalism? What were his thoughts in this regard?

VM Ravi Kumar (VMRK): There are three important pillars of Dr Ambedkar’s ecology, as I call it.

First, Ambedkar looks at humans and Nature from a democratic perspective. That is why I term it as ‘Ambedkar’s ecological-democratic thought’.

For Ambedkar, democracy is a paradigm of thought and human life. He perceives democracy as a ‘mode of living’. If democracy is defined as a mode of living, then there has to be a democratic principle in the distribution of natural/ecological resources to humans. This means the resources of Nature shall be made accessible to all sections of human society. That has been an underlying principle that Ambedkar mentions in most of his writings.

In simple terms, Ambedkar is perhaps the first person in India who looks at the allocation of ecological resources to humans through the principle of democracy.

For Babasaheb, democracy is not just confined to the ballot box or the political system. Rather, it has to be a guiding framework for allocation of natural resources to all sections of humanity. This has been an uncompromising standpoint that Babasaheb adhered to in his life.

Second, for Ambedkar, ecological crises are essentially social crises.

For him, social hierarchy is a universal phenomenon. This social hierarchy is responsible for the appropriation of ecological and natural resources into the wealth-making process, however in a disproportionate way.

So, for Ambedkar, the wealth-making process across the globe, including India, happens to be the one where the privileged sections of human society gained a disproportionate access to the resources of Nature while underprivileged ones could not gain adequate access to resources.

This is called ecological equity and is the central pillar of Dr Ambedkar’s ecological schema.

The third pillar is about how to handle such ecological crises. Ambedkar was a very pragmatic philosopher. He was not just concerned about what had been happening. Rather, he tried to change how society functioned.

Ambedkar’s ecological thought has a wonderful scheme for democratisation of natural resources in case of the Indian subcontinent. He says the democratic morality in our nation-state, the Constitution and the democratic apparatus is a unique opportunity in India to redistribute the resources of Nature which were disproportionately distributed in traditional, conventional Indian society.

His main contention is that we have to come up with strategies, policies, values and attitudes rooted in the principle of equity so that the ecological injustice done to India’s social structure can be mitigated. This can be done through constitutional morality and public policy in order to make ecological resource distribution more egalitarian and equitable.

A strong society is possible when the entire populace develops by gaining more equitable access to natural resources.

I would like to add that Ambedkar was not just happy with normative, constitutional policy which is seen as some kind of agency to develop Indian society.

Rather, he was equally concerned with the moral dimension of human society. His 1956 work, The Buddha and his Dhamma reflects a very deep commitment on his part for the creation of an ecologically democratic society within the moral framework.

The work says that it is not enough to have equality and liberty. There should also be fraternity. The Buddha gave importance to ecological conservation. By quoting the Buddha, Ambedkar clearly mentions that human beings should not just be restricted to equality among themselves but should go beyond that. He contemplates the notion of ‘biocentric equality’, which means equality among all species.

Ambedkar is popularly viewed as a modern thinker who does not care about Nature or ecology. This is not true. Through my work, I have tried to dismantle that notion and fit Ambedkar into the process of ecological conservation.

However, there is a difference between (M K) Gandhi and Ambedkar in terms of looking at the relationship between human and nature. Gandhi uses tradition and an agency for defining the relationship between human and ecolog. For Ambedkar though, ecological conservation is not necessarily just about tradition but is rational and scientific as well as moral.

Read Relevance of Gandhian environmentalism

Thus, Ambedkar represents a unique voice within Indian environmental thought which says that to address socio-ecological problems, we need tradition, rationalism and science as well.

RG: How different is Ambedkarite environmentalism from classical Western environmentalism, say that advocated by Rachel Carson, for instance?

VMRK: Ambedkarite environmentalism is more of agrarian environmentalism while what you are referring to (Euro-American environmentalism) is essentially urban/industrial environmentalism.

Let me explain. Ambedkar’s perspectives developed vis-à-vis India and South Asia mostly in the 1940s when this region had relatively less urbanisation. We thus had very few problems related to air, water and other forms of pollution and other urban aspects like what we have right now.

Therefore, Ambedkar’s conceptualisation of environmental thought is essentially aimed at addressing agro-ecological problems, unlike Euro-American Environmentalism.

Agro-ecological problems have certain underlying points. For instance, Ambedkarite agro-environmentalism says that land reforms are needed. From the 1920s, Ambedkar stressed that land distribution in India was skewed. Land has to be accessible to most subaltern sections. He urges upon the Government of India to redistribute land.

Second, he talks about India’s indigenous cattle population. He says we need to conserve cattle in a very judicious way.

Writing in 1930s, he said a healthy agrarian economy in India will not be possible unless there is a healthy cattle population which will provide energy in the form of cow dung, draught power of bullocks and the like.

Third and very important, he talks about management of water. Ambedkar claims water — potable or irrigational — has not been available to the majority of Indians because of social hierarchy and ritual traditions.

Right from 1927 onwards, when he launched the Mahad Satyagraha — the first for water struggle — he consistently advocated that the state has to play an important role in democratisation of access to water.

Most of his writings from this period exhort the state to create water facilities in Dalit localities and villages.

He is also the architect of large water projects in India like the Damodar Valley Corporation Project. This means that Ambedkarite water policy can be seen right from village to national level with focus on equity.

Another important environmental advocacy seen in Ambedkar’s writings is his emphasis on afforestation. In 1942, he wrote a small piece where he said if the Depressed Castes Association comes to power, it will promote afforestation actively.

He mentions that the vibrant rural economy is not possible without afforestation since it is important for wood requirements and livestock grazing. Ambedkar was perfectly aware about the conservation of village commons, be it grasslands, common lands and village forests. Conservation of village commons is thus an important part of Ambedkarite environmentalism.

Last but not the least, he proposes a very peculiar idea which has not gained currency in the existing literature: Separate settlements.

From 1947, he advocates that separate villages need to be created for Dalits. Traditional Indian villages are centres of oppression for Ambedkar. Most also do not have space or resources for Dalits because of social stigma.

He proposes that the Government of independent India should levy cess and use it in order to create separate settlements so that untouchability goes away.

Ecological reforms are thus seen by Dr B R Ambedkar as one of the tools for eradication of untouchability and a very important strategy to develop an inclusive Indian society.

That is where the difference between Ambedkar and traditional thinkers comes in. These thinkers advocate that ecology needs to be conserved for moral considerations, cultural impulses and spiritual pursuits.

But Ambedkar wants to conserve and use ecology for human emancipation and progress. Ultimately, there has to be a sustainable relationship between ecosystems and the needs of humans.

Ambedkar’s environmentalism is thus ‘anthrobiocentricism’. Ecological thinkers are either anthropocentric or biocentric. Both are extremes. Ambedkar offers a very rare and unique combination of both streams of thought. He says Nature is very important. At the same time, it has to be used for eradicating socio-economic inequalities and creating a democratic society.

RG: How can Ambedkarite environmentalism help the world face the challenges of the ongoing climate emergency?

VMRK: I think somewhere we are being trapped by the neo-orientalist framework which says that Indian ecological thought is essentially traditional, spiritual or metaphysical.

Here, Ambedkar provides a very important intervention when he says that Indian environmental thought is not necessarily spiritual or traditional. It has very vibrant material and moral dimensions.

Right from the Buddha till his own time, Ambedkar tries to prove that Indians are very much concerned for conservation of natural resources — not as a spiritual duty but rather as a moral compulsion of human society.

Timothy Morton has coined the term ‘dark ecology’. He says if we don’t understand climate change, we are doomed to perish. Ambedkar somehow understands that in the 1940s and 1950s.

Read Book Excerpt: Ashoka, the ‘vegetarian king’

He writes that unless you devise a very efficient and effective policy framework for the management of ecological resources, their optimum and sustainable use is not possible.

Ambedkar thus advocates a very formidable ecological governance based upon democratic principles. He realised such governance was not possible without changing people’s attitudes.

That is where The Buddha and his Dhamma creates a new eco-value system of Neo Buddhism. We have to use natural resources in a very judicious way and to the extent they are capable of providing us continuous access to resources.

The ongoing climate crises can be seen thus from an Ambedkarite perspective. The democratic principle is very important. And it is applicable at the international level — what is known in climate politics as ‘equity’.

We thus have to discourage the ongoing excessive consumerist culture, which is something Ambedkar stands for. At the same time, in order to make efficient use of a public policy framework for management of ecological resources, Amedkarite philosophy talks of attitudinal change and a spiritual dimension, though not in a normative sense. Ambedkar says humans should concern for their fellow humans, not for a supernatural power.

I believe climatic crises can be handled by Ambedkarite principles like democratic governance and moral spiritual humanism.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.