For a decade, 200 villages in Odisha have conserved and grown 190 indigenous rice and millet varieties with proven climate resilience

The pride and excitement were evident among the women at Hurlu village in Odisha’s Rayagada district as they congregate in a sprawling courtyard to display a colourful array of seeds to Down To Earth (DTE). It is early February and yet, temperatures have begun to rise in various parts of the state. But the weather at Hurlu is still pleasant, as if to reflect the spirit of its inhabitants.

Soon, the women decorate one cot with red, black, white, green, yellow and grey seeds, neatly placed in bowls made from sal leaves. “These are the native varieties of kuyan (pearl millet), dokin (sorghum), kode kanga (cowpea), arka (foxtail millet) and dangrani (a type of pulse),” says Kirko Kilaka, a 70-year-old resident of Hurlu. Seeds on the other cot are of indigenous paddy varieties that the residents refer to, in their native language, Kui, as kanda kuli, dhangri mali, basna kuli and bodhana.

The 100-odd tribals in Hurlu village, belonging to the Talia Kondh, a sub-tribe of the Kondh Adivasi community, show how powerful indigenous knowledge can be. Not just Hurlu, all tribal communities in the region treat land as a living entity, intertwined with their cultural identity.

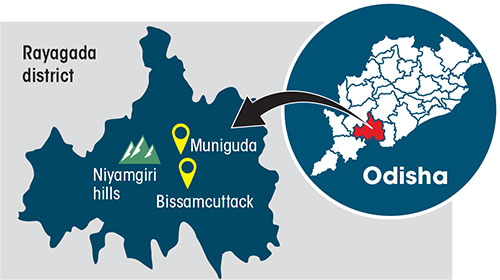

Over the past decade, villages in the forested foothills of Niyamgiri have identified, revived and are cultivating as many as 190 such traditional varieties or landraces of paddy and millets, which have demonstrated climate resilience and are resistant to pest attacks, according to Living Farms, a non-profit working with farmers in Bissamcuttack and Muniguda blocks of Rayagada.

“Paddy varieties like bodhana and kanda kuli do well even when there is not enough water. And it is never a total loss, even in the case of a crop failure. The suan variety grows well even in low water conditions, with little moisture in the soil,” Kirko Kilaka tells DTE. “Our native varieties are also rich in nutritional content,” says Bindri Kradika, an octogenarian and the oldest woman in Hurlu.

These revived seeds are just a fraction of the varieties that communities in the region grew before the 1960s, when the Green Revolution transformed agriculture, says Bichitra Biswal, senior programme manager at Living Farms.

Carved out of undivided Koraput in 1992, Rayagada is located in the Jeypore tract of the Eastern Ghats. According to a 2020 review article published in Oryza, an international journal on rice, Jeypore tract with its diverse rice forms is considered the earliest independent rice domestication region of aus ecotype—the aus group of Asian cultivated rice that has unique alleles for biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and high genetic diversity. In fact, the review article states that the aus type fragrant rice is the original crop of Indian subcontinent, domesticated in hill areas by primitive tribes around 4,500 years ago. “Undivided Koraput historically had 30,000 indigenous varieties of rice. Some people believe that up to 100,000 rice varieties were being grown in the region,” Biswal says.

These traditional varieties, however, could not compete with the high-yielding varieties (HYVs) that were being aggressively promoted under the Green Revolution. That was also the time when commercial plantations of eucalyptus, previously alien to the region, had begun to meet the requirements of paper mills. Soon, the landraces of both paddy and millets fell out of favour.

These traditional varieties, however, could not compete with the high-yielding varieties (HYVs) that were being aggressively promoted under the Green Revolution. That was also the time when commercial plantations of eucalyptus, previously alien to the region, had begun to meet the requirements of paper mills. Soon, the landraces of both paddy and millets fell out of favour.

“Selling and buying seeds was never part of our culture. Our seeds are a gift from Mother Earth. But this changed as we started growing the high-yielding varieties,” recalls Bindri Kradika. Over the years, as people became reliant on commercial seed suppliers, the traditional seed varieties and the practice of storing them were forgotten.

“Before the 1960s, some 70-75 millet varieties were cultivated in Bissamcuttack and Muniguda blocks. By the early 2000s, only seven or eight native millet varieties were being cultivated across the district. In fact, the total crop varieties being grown across the region were limited to just 10 to 15, with each village growing a maximum of three crops,” says Biswal, adding that the disappearance of native crops and reducing diversity had an impact on the food and nutritional security of people.

The final blow came from the increasing frequency of extreme weather events. The state has been battered by natural calamities in 41 of the past 50 years; 19 years were marked by drought, as per Odisha’s State Drought Monitoring Cell. “We saw frequent droughts between 2000 and 2010. The widely distributed and promoted varieties succumbed to their impacts. In contrast, the native landraces showed resilience to extreme weather,” says Gaijmaji Kradika of Hurlu.

Around 2010, the region saw a movement of sorts to identify the forgotten landraces and bring them back to the fields. But the process was long and arduous. “This was expected. Our forefathers used to say that seeds should never be lost, as reviving them is extremely difficult,” says Kirko Kilaka.

Coordination is key

What aided the revival efforts was constant communication among communities in the region. Initially, the elders in Hurlu picked up the baton and went to upland villages to explore what seeds were available with them. Living Farms also played a role by surveying villages in Bissamcuttack and Muniguda blocks and identifying households that still possessed or grew heirloom seeds.

“Soon conversations about traditional crop varieties and exchanging seeds among communities became the norm,” says Krishna Kahnar from Dakulguda village, 20 km from Hurlu.

Further, Debal Deb, an ecologist and conservationist who has conserved 1,500 indigenous rice varieties, distributed seeds of 30 native varieties in Bissamcuttack and Muniguda blocks.

Gradually, native seeds were grown again. In the initial years, on advice from Living Farms, communities sowed HYVs and native seeds on different plots to compare growth and health in varied weather conditions. “The difference was apparent in 2013, for example, during the flowering time of paddy. The crops needed to be irrigated, but rain had not arrived yet. While indigenous paddy was in good shape during harvest, the Lolato Konarko HYV was not,” says Ravindra Kilaka of Togapadar village, 3 km from Hurlu.

Biswal recalls another example in 2017, when paddy in almost all of Odisha was attacked by a pest called leda poka (a swarming caterpillar). The pest did not cause much damage in areas with native varieties. “These areas followed a multi-cropping system, while pests and insects are drawn to monoculture,” adds Ravindra Kilaka. Gradually, the biodiversity of colours and textures returned to fields and diets.

Even now, every Tuesday, residents of these villages meet at the haat (weekly market) in Dukum panchayat to exchange notes on the performance of seeds, their availability and what to sow when.

In Hurlu, the movement also led to the development of a seed bank, as well as preservation in households. The village residents choose the best seeds from plants that are optimal in size, have fruited well, get the maximum nutrient input and are not attacked by pests. Most of the seeds are hung just directly above the area were food is cooked, so that an optimal temperature is maintained.

People are also mindful of the requirements of different crops. For example, pigeon pea and cowpea seeds must be mixed with ragi and cashewnuts, respectively, to evade diseases and pests.

With the revival of indigenous crop varieties, communities in the 200 villages have reinstated the traditional food security model that ensures round-the-year food availability. In Hurlu, for instance, suan or barnyard millet is sown in May and harvested during July-August, at a time when no other grain is available. The millet’s importance as the first food in the house is best captured in a Kui phrase popular in the village and translated in Hindi as, ‘dukha time me mama hai, bhookha time me suan hai’ (In difficult times, the mother’s brother comes to the rescue and during hunger, suan does). In August, a variety of little millet is sown that can be harvested by the first week of December. “This little millet crop can survive on just dew drops,” says Kani Kumbrika from the village. Then there are ragi varieties, called mandya in Kui, sown in June. The boda mandya variety is harvested in September, dasera mandya in October and diwa mandya in November. This system provides a fail-safe option to sustain people in case one harvest fails. A similar model is used for pulses and oilseeds.

To ensure that the heirloom seeds do not once again sink into oblivion, elders in the villages are trying to create interest in the issue among the younger generation. “The seed business has inculcated a habit of procuring any variety from the market, and the knowledge of maintaining genetic purity and diversity has been eroded. This trend is seen across India,” says Deb, adding, “Younger generations have even forgotten names of different varieties.” Seed revival efforts can be seen in tribal areas of Chhattisgarh’s Bastar region, northern Karnataka, southern Maharashtra, Nagaland, Tripura, Manipur and Mizoram. But in Rayagada, the movement inspires hope as it cuts across generations.

This was first published in the 16-30 April, 2024 print edition of Down To Earth

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.