Developed countries provided and mobilised more than $100 billion in climate finance to developing countries in 2022, after failing to do so in previous years. This is according to a new report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an international organisation made up of the 38 most economically developed countries.

According to the report, $115.9 billion was allocated to developing countries to support climate action in 2022. “This achievement occurs two years later than the original 2020 target year, but one year earlier than in projections produced by the OECD,” the report read.

In 2009, developed countries committed to providing $100 billion annually in climate finance by 2020 to help the developing world mitigate and adapt to climate change. Also, per Article 9 of the Paris Agreement adopted in 2015, developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country Parties concerning both mitigation and adaptation.

However, others have raised doubts about the OECD report. “While developed countries claim to meet the target of providing $100 billion annually in climate finance to developing nations, the process is riddled with ambiguity and inadequacies,” Harjeet Singh, a climate activist, said in a statement.

“We need more transparency in the accounting and reporting framework, especially since there is no agreed-upon definition of climate finance and what needs to be counted as part of it. These figures will have to be scrutinised further,” Sehr Raheja, programme officer for climate change at Delhi-based think tank Centre for Science and Environment, told Down To Earth.

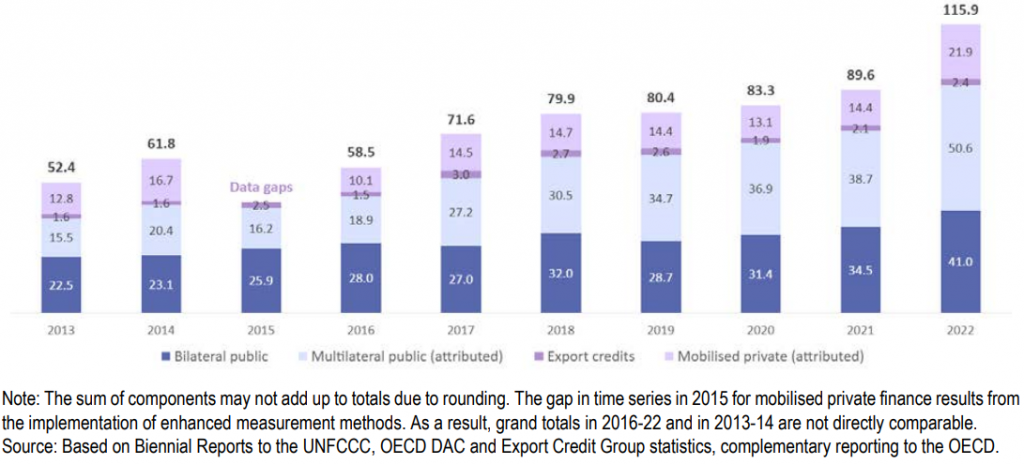

Climate finance can come from public, private and alternative sources of financing. The OECD report noted public climate finance, drawn from bilateral (countries) and multilateral sources (like World Bank) accounted for close to 80 per cent of the total financial flow in 2022. This figure increased from $38 billion in 2013 to $91.6 billion in 2022.

Bilateral sources funnelled $41 billion while multilateral sources provided $50.6 billion in 2022. Mobilised private finance accounted for $21.9 billion in the same year.

Private finance mobilised by public climate finance grew from $14.4 billion in 2021 to $21.9 billion in 2022 — a 52 per cent jump. This followed several years of relative stagnation, the report pointed out.

The energy sector benefited the most from private mobilisation in 2022 and middle-income countries received the most investments.

Most climate finance went to mitigation. Adaptation activities received $32.4 billion in 2022. Progress, however, has been made, compared to 2016’s figure of $10.1 billion.

Of the $32.4 billion, $28.9 billion was from bilateral and multilateral public sources, while financing mobilised from the private sector amounted to $3.5 billion in 2022, growing from USD 0.4 billion in 2016.

Loans continue to make up much of the financial flow, which is already pushing developing countries into a debt trap. Some 70 per cent of the public climate finance provided bilaterally and through multilateral channels were in the form of loans. This trend is similar to the previous years. Only 28 per cent were provided as grants.

Lower-income countries accounted for 64 per cent of total public climate finance provided as grants, while for lower-middle-income countries, grants made up only 13 per cent of the share, the data showed.

Much of the funding, Singh added, is repackaged as loans rather than grants and is often intertwined with existing aid, blurring the lines of true financial assistance.

Between 2016-2022, close to 90 per cent of financing provided by multilateral developmental banks (MDBS) took the form of loans. The same applies to bilateral providers, with 57 per cent as loans and 39 per cent as grants.

Multilateral climate funds, on the other hand, provided 54 per cent as grants and 39 per cent as loans, both of which tend.

“Meeting an unambitious objective with an outrageous delay is not something to be congratulated. Loans are again taking the lion’s share of climate finance, which goes against any concept of climate justice,” Rebecca Thissen, global lead for multilateral processes at Climate Action Network, said in a statement.

The $100 billion goal is not based on the needs of developing nations. Emerging markets and developing countries other than China require $1 trillion per year in external finance by 2030, according to a 2022 report by the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance.

This goal will be replaced by the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance, which shall be set from a floor of $100 billion per year before 2025. Nations are negotiating the new goal’s timeframe, structure, quantum and sources of financing.

“A lot of work has been done over the two years to identify components of the goal, which has to be agreed upon by the end of this year. We are at the halfway point of the year and divergences in basic elements such as who will contribute and receive funding remain. It is going to be a tricky road forward,” Raheja noted.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.