Decentralised planning designed to deliver outcomes are needed for water equity in dense, unplanned settlements

This is part 2 of a two-part series on water for our cities

How do we define a “Water Sensitive City” (WSC) or a “Climate Resilient City” with water at its core? Can it be done abstractly? It certainly cannot be defined in a way that incorporates everything without prioritising actions.

In the first part of this series, we discussed the discourse on Water Sensitive Urban Design and Planning (WSUDP). Who benefits from WSUDP and how should perhaps guide the theory and practice of WSUDP or WSC framing for cities in the Global South.

We then proposed the necessity of a city water and sanitation plan. This entails a long-term plan for each city, aimed at achieving water equity and justice. Identifying hotspots or problem areas for groundwater, water supply, wastewater, and stormwater will inform the development of a WSUDP or WSC vision and plan.

This approach shifts focus away from individual projects and detailed project reports towards a city-wide reimagining of water supply, wastewater, and stormwater solutions. For example, a 20-year water security vision for a city could include a roadmap of interventions every five years.

In 2022, Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) proposed a water-sensitive cities framework for the Global South, identifying four parameters or indices for progress towards becoming water-sensitive.

These parameters were: Functional infrastructure for water supply and sanitation (addressing breakdowns and underperformance in existing infrastructure); functional and inclusive infrastructure (ensuring accessibility for all, including the less privileged); reuse of treated wastewater and biosolids (a priority for the water, energy, and nutrient-deficient Global South, where faecal waste is a valuable resource for agriculture).

CSE tested the WSC framework in 2023 through primary research in Sangam Vihar, a densely populated, unplanned urban settlement in Delhi. The aim was to understand how Delhi could achieve a water-sensitive city outcome, with equity and justice as guiding principles.

Informal and unplanned settlements now dominate the urban landscape of most developing countries in Africa and Asia, especially in metropolitan cities. Water conservation and septage management can be addressed in smaller towns and peri-urban settlements through in-situ groundwater recharge and non-sewered sanitation systems. However, what about large metros and state capitals with high percentages of unplanned and informal settlements?

There are many such questions that need answers: Can existing problems of low per capita water supply and high volumes of greywater, black water, and stormwater from such large, dense settlements be addressed with one-off retrofitting solutions? Is sewerage-based retrofitting to existing main sewer lines feasible for a settlement of over one million people?

Further, we must ask if its water supply deficit can be met by ad hoc augmentation from existing, failing sources, considering the political economy of the water sector? Can stormwater and flooding challenges be addressed merely as drainage issues? If not, what is needed to tap into this as a water conservation resource?

Read more: Securing water for Delhi: Looking beyond the numbers game

The study encountered several challenges. The first was documenting the existing status of water supply, sanitation, and stormwater systems, which was complicated by the lack of data sources. Enumerating the population and their per capita water supply through a primary survey of 13 blocks was necessary.

Once we clarified the population and their existing per capita water supply, we could estimate grey and black water production. We then assessed the feasibility of the sewers being laid in Sangam Vihar — the dimensions of the sewer pipes needed to convey this volume of wastewater through only two peripheral sewer lines to the main sewer line on Mehrauli Badarpur Road.

Reimagining decentralised water supply for Delhi’s unplanned settlements

Sangam Vihar has a low water supply of 45 litres per capita per day (lpcd), far below Union Ministry of Urban Development’s Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation standard of 135 lpcd. The low volume of per capita water supply, affordability, and water quality issues have contributed to the rise of a ‘water mafia’ that controls the water supply and distribution networks.

The so-called ‘water mafia’ in Sangam Vihar controls all three water supply sources: Borewells, tankers, and piped water supply. Augmenting the piped water supply can eliminate this issue.

Water supply is not only very low (45 lpcd) but also highly dependent on groundwater from borewells. Any drop in groundwater levels can lead to severe water scarcity and high economic burden, as observed in the summer of 2024, when water tankers could not meet the water needs of the unplanned settlements.

The 5 square kilometre area of the 13 blocks of Sangam Vihar is highly concretised and built up, hindering in-situ groundwater conservation and recharge. The forest areas on its periphery, with their small water bodies, provide opportunities for groundwater recharge.

Read more: Bengaluru only needs urgent institutional makeover of its water utilities

If decentralised sewage treatment plants (STP) are built around Sangam Vihar (in the peripheral forest and open areas), the treated wastewater and stormwater from area can be used to fill existing water bodies for groundwater recharge, thereby ensuring groundwater supply for non-potable purposes.

Ensuring water equity and justice

A reimagined city-wide decentralised water supply system using treated wastewater to recharge a few large lakes, allocating them for water supply to nearby areas, can ensure water equity and justice for dense, unplanned urban settlements.

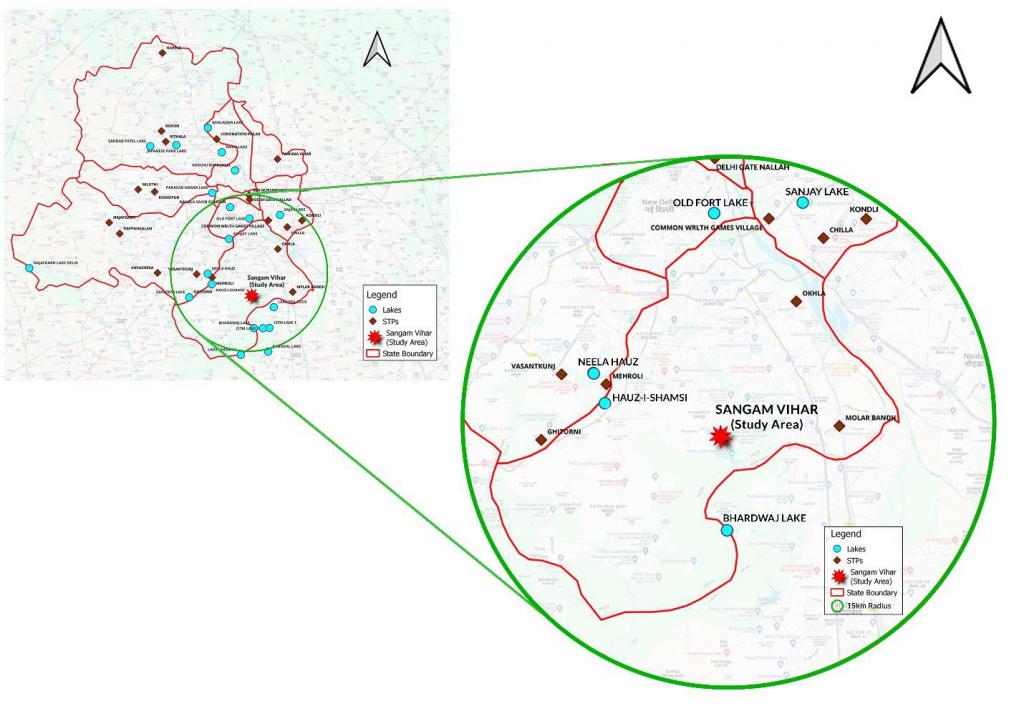

The CSE study mapped a 10-15 km radius of Sangam Vihar to identify large lakes and nearby STPs. Lakes exceeding 2 hectares (ha) include Hauz-i-Shamsi lake (2.85 ha), Neela Hauz lake (3.65 ha), Old Fort lake (5.30 ha), Bhardwaj lake (11.8 ha), and the largest one, Sanjay lake (74.5 ha).

STPs and lakes surrounding Sangam Vihar

Source: CSE

This visual depiction aims to locate the areas from which the treated wastewater can be obtained. The bigger lakes, which can be used for recharge and water supply (with secondary and tertiary treatment) to nearby colonies, planned and unplanned. This way, Sangam Vihar water security can also be enhanced with an assured nearby water supply from recharged lakes, instead of depending on high-cost pumping and supply from faraway sources.

The urban water crisis of Delhi and other global south cities, is a crisis of equitable and just distribution, of the political economy of water and waste water management in our cities. It is not about the absolute scarcity of water. However, with the steep rise in population of Delhi in the last decade to nearly 30 million today, there is a need to review the current 1,000 million gallons per day water share of the capital.

We need to remind ourselves that 45 litres per capita a day is all that a million plus residents of Sangam Vihar in Delhi are getting (and there are several other such settlements), while some of us are getting five to ten times this supply. This needs to be set right.

Read more: Global South water-sensitive cities: Framing the discourse

Our large metropolitan cities with significant numbers of unplanned and informal settlements need reimagined decentralised and co-located water supply and wastewater treatment systems, along with infrastructure redevelopment to facilitate multiple reuses of treated wastewater to meet growing water demands.

Small and medium-sized cities should also start planning for decentralised systems with a reuse plan, focusing on justice and equity outcomes rather than purely technical solutions. The era of large, centralised water and sanitation systems is over.

Decentralised systems alone may not ensure water justice and equity unless they are designed to deliver these outcomes, as suggested for Sangam Vihar. This approach, combined with infrastructure re-engineering for decentralised water supply, sanitation, and stormwater management, along with institutional and governance reforms to manage all surface and groundwater, can contextualise a WSUDP or WSC perspective for Global South cities.

Read more:

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.